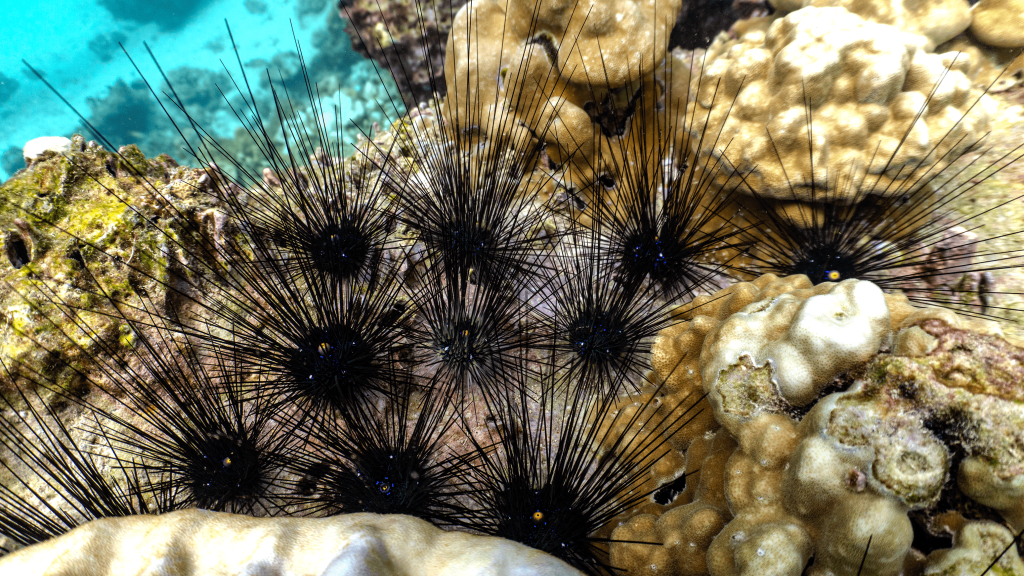

Long Spined Black Urchin

Long Spined Black Urchin

The Long Spined Black Urchin (Diadema antillarum), also known simply as the long-spined sea urchin or the black sea urchin, is a member of the Diadematidae family.

Although the Long Spined Black Urchin may seem intimidating due to its long spines, it plays a vital role in maintaining coral reef ecosystems. These sea urchins prefer warm, shallow areas, typically at depths ranging from 3 to 10 meters. They hide in crevices, exposing only their spines, although they can sometimes be found in more open areas. At night, they move about a meter away from their shelters to forage for food. They are extremely sensitive to light, thus choosing locations with sufficient shade.

The main feature of Diadema antillarum is its spines, which are typically 10-12 cm long, and can reach up to 30 cm in large specimens, whereas most sea urchins have spines 1-3 cm long.

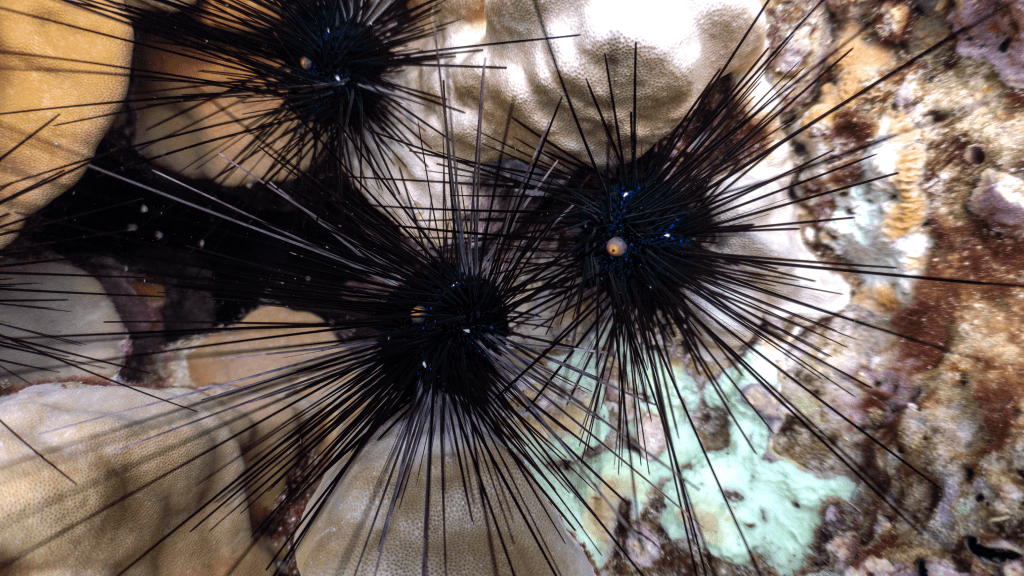

The spines of these urchins are very brittle and can break off, lodging in predators that attempt to attack them. They are also covered in a venomous substance that deters small predators. [Note: Injuries are primarily from puncture wounds and irritation, though the source mentions a venomous substance].

Sea urchins are among the most ancient creatures in the ocean, existing for over 450 million years, which predates the dinosaurs by 200 million years. They belong to the echinoderms, meaning 'spiny skin,' which also includes starfish, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers (holothurians). Virtually all echinoderms have five identical body parts (radial symmetry), and the Long Spined Black Urchin is no exception. Beneath its spines, one can see five calcium carbonate plates that support the urchin's body (test).

The name 'Long Spined Black Urchin' comes from its long black spines [Note: Spines are typically black, sometimes with banding in juveniles, but not usually white]. It moves across the reef using tube feet, which operate on a hydraulic principle. By drawing water through their water vascular system, urchins inflate and extend their tube feet, allowing them to move and gather food.

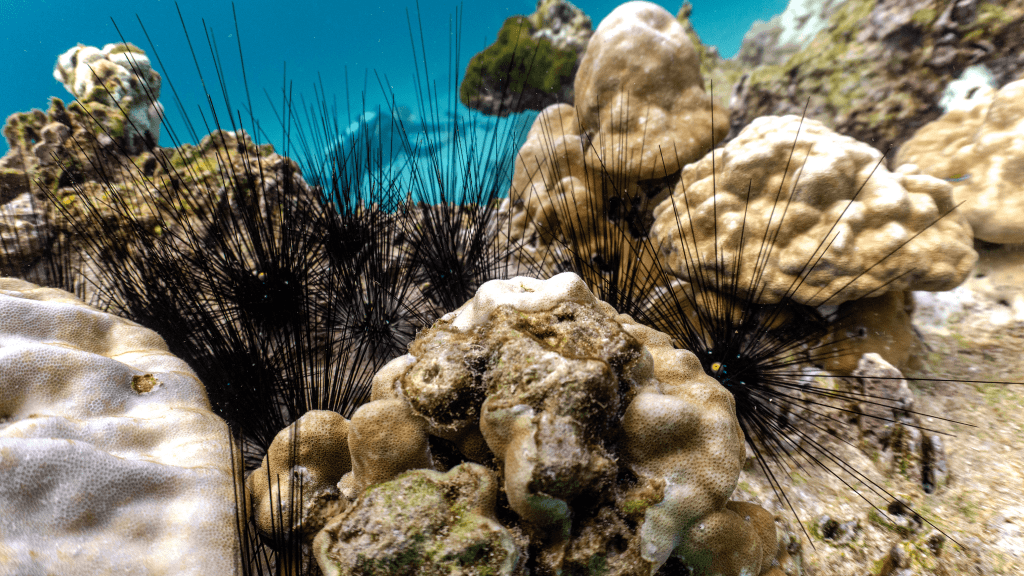

Long Spined Black Urchins reproduce through broadcast spawning from July to September, releasing their gametes into the water column. The larvae, called echinoplutei, float freely and can travel long distances via ocean currents before settling onto new reefs. After 4-6 weeks, the larvae mature, losing their swimming structures and developing long spines, enabling the urchins to disperse over considerable distances.

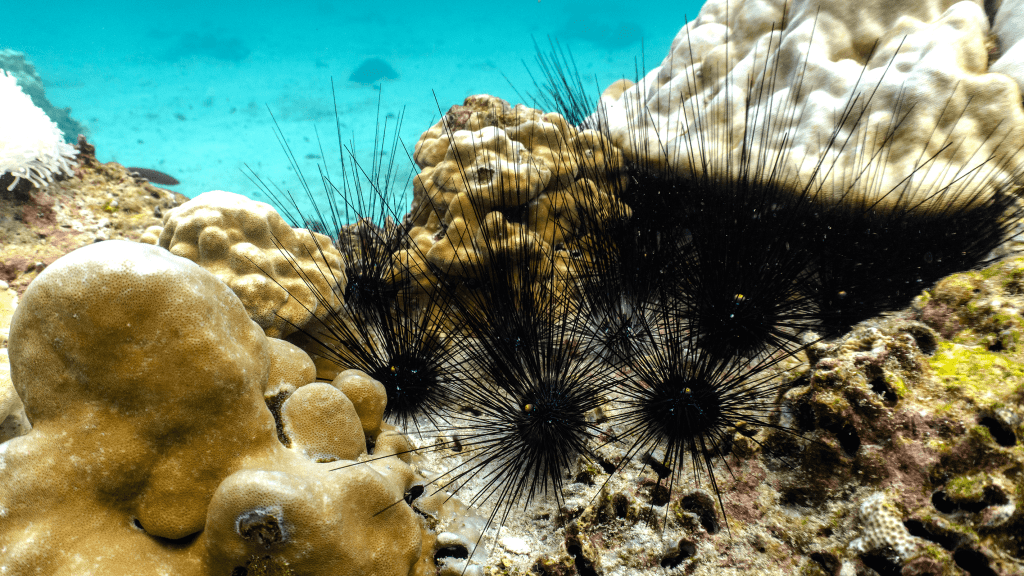

These sea urchins are voracious algae eaters, earning them the nickname 'lawnmowers of the ocean'. Daily, they clear reefs of algae, creating conditions for coral growth and maintaining the reef ecosystem.

Diadema antillarum remains one of the most abundant and ecologically significant shallow-water sea urchin species in tropical regions. It can be found in the tropical waters of the Western Atlantic, including the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the coast of South America down to Brazil, as well as in the Eastern Atlantic around the Canary Islands and in the Indian Ocean. These urchins help control the overgrowth of algae that can smother coral reefs.

The population of Long Spined Black Urchins in the Caribbean significantly declined in 1983, leading to devastating consequences for the reefs. The causes of this die-off are still debated, but possible factors include climate change, water quality issues, and diseases linked to untreated wastewater discharge.

The mass mortality of the urchins led to an overgrowth of algae, smothering corals and preventing the settlement of new coral larvae. This caused a 'phase shift,' where coral reefs became dominated by algae. Without sea urchins, this situation could become irreversible.

Despite these challenges, there are reasons for optimism. Scientists are actively working on restoring the Long Spined Black Urchin population, and by supporting reef protection, we can help them recover.