Dry Suit: Diving in a Dry Suit

Features, training, and first experience diving in cold water

Home/Blog/Dry Suit: Diving in a Dry Suit

Introduction

When I left Thailand, I had no idea when or where I would dive again. It felt like I had to say goodbye to diving for a long time. Belgrade is not by the sea, and the closest convenient diving location is neighboring Montenegro, where the season lasts only six months a year and trips require planning in advance. But I wanted to dive more often...

After three months without diving, I finally found a way to continue, even in my current situation. To do that, I had to learn how to use a dry suit - without it, winter diving would be very difficult. Luckily, I like learning new things 😊

I'm not an expert in dry suit diving yet, but I understand the basics and want to share my experience.

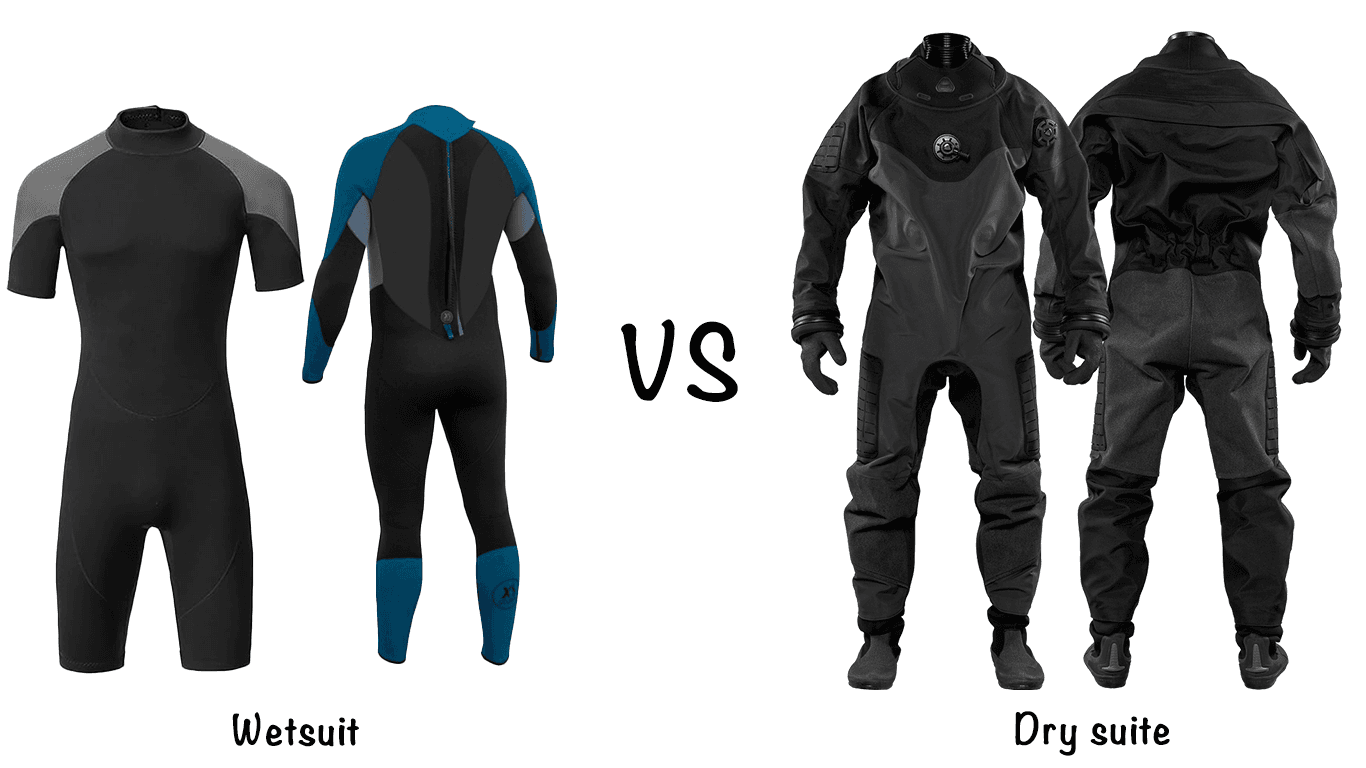

The Difference Between a Dry Suit and a Wetsuit

The difference seems obvious: in a wetsuit you get wet, in a dry suit you stay dry. Magic? Almost ✨

But the difference is not only about staying dry. Wetsuits are simpler and allow more freedom of movement. In a wetsuit, a thin layer of water stays between your skin and the neoprene and warms up from your body heat. Most divers dive in wetsuits.

A dry suit, on the other hand, is completely sealed and isolates your body from the water. Using it requires additional skills, preparation, and maintenance. There is also a big price difference. Dry suits are more expensive, but with proper care they can last for many years. It's more of an investment than a simple purchase.

The main difference is temperature range. Depending on thickness and personal cold tolerance, wetsuits work well in tropical and moderate climates. But below 10°C, additional protection becomes necessary --- and this is where dry suits are essential.

What Is a Dry Suit and Why Is It Used?

A dry suit is special diving equipment that allows a diver to remain dry underwater.

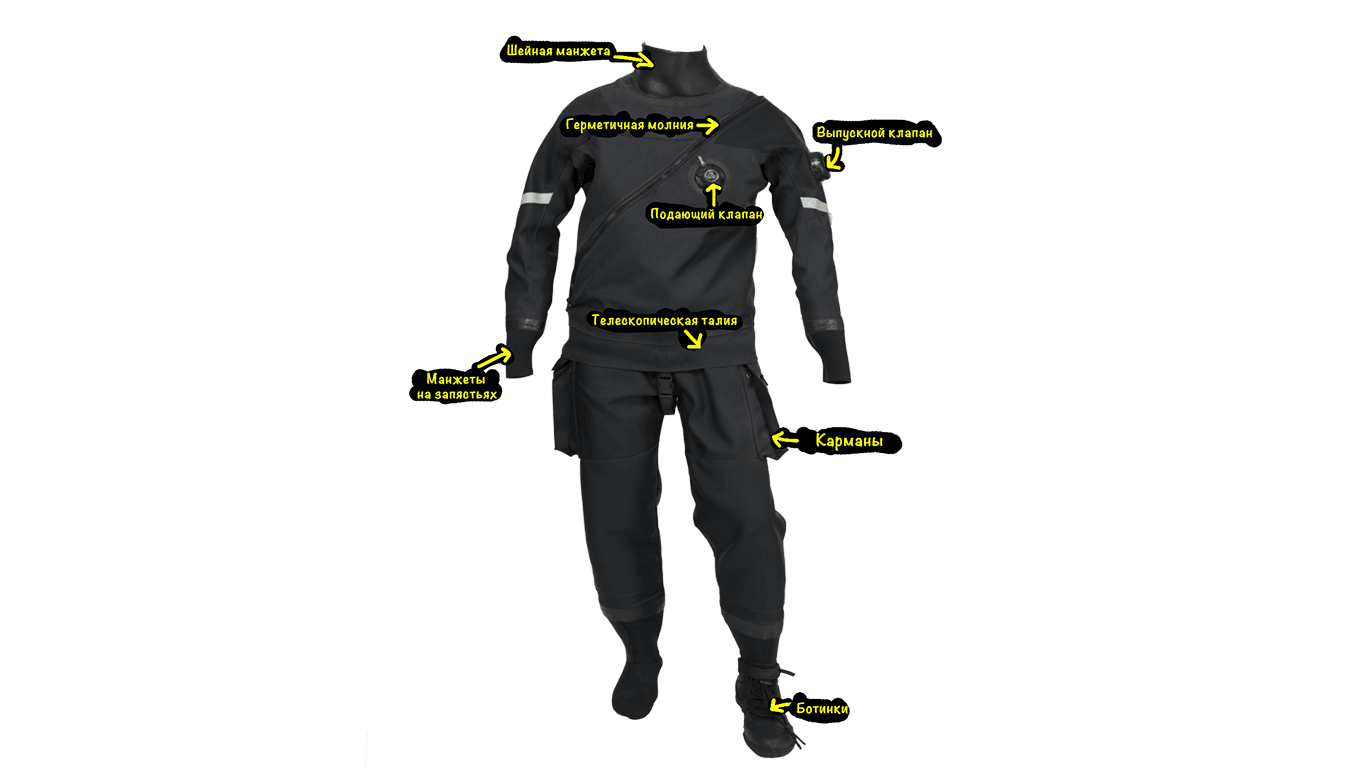

Main Elements of a Dry Suit

Waterproof Design

Dry suits come in two main types: membrane and neoprene.

Membrane suits are lighter and more flexible but require proper undergarments for insulation. Neoprene suits are warmer but slightly restrict movement.

To prevent water from entering, dry suits use tight seals at the neck and wrists. Modern dry suits would not exist without waterproof zippers. Regular zippers let water in, but waterproof ones are based on sealed zipper technology originally developed for space suits. Real rocket science! And yes, the zipper is the most expensive part of the suit.

Insulation

Air inside the suit helps keep you warm, but it is not enough on its own. That's why you wear thermal undergarments underneath. The colder the water and the longer the dive, the warmer your undergarment should be.

There are many options - from simple solutions to professional systems.

Valves

The key tool for buoyancy control in a dry suit is the valve system. Air is added through the inflator valve (usually connected to the tank), and excess air is released through the exhaust valve.

Gloves, Boots, Hoods, Pockets

Additional elements like gloves, boots, hoods, and pockets make diving more comfortable. Pockets are especially useful for carrying items you might need underwater.

When Do You Need a Dry Suit?

A dry suit is used in:

- Cold water diving (below +10°C), when a wetsuit no longer provides enough comfort.\

- Long dives, because it keeps you warm for extended periods.\

- Challenging conditions, such as icy water, polluted water, or strong currents, where staying dry and protected is important.

Usually, air is used inside the dry suit. In technical diving, argon may be used because it provides better insulation. Argon has lower thermal conductivity than air, so it helps retain heat longer.

Proper undergarments also play a huge role. With the right setup, you can dive comfortably even in icy conditions.

Types of Dry Suits

There is no universal "best" dry suit. The right choice depends on your needs, conditions, and preferences.

Membrane Suits

Membrane suits consist of several layers, with a waterproof membrane in the center. The most common material is trilaminate, originally developed for military use.

Trilaminate suits are durable, long-lasting, and dry quickly. They are lighter and easier to transport compared to neoprene suits (though still bulkier than wetsuits).

However, membrane suits provide almost no insulation, so choosing the right undergarment is very important.

Neoprene Suits

Neoprene dry suits are similar to wetsuits but fully sealed to prevent water from entering. They provide basic insulation, so in warmer water you might not need thick undergarments.

They are elastic and comfortable but require more weight due to positive buoyancy. Insulation decreases slightly at depth, and they dry slower than membrane suits.

Over time, neoprene also loses some of its properties.

Hybrid Models

Hybrid suits combine features of membrane and neoprene suits. They are lighter than neoprene and warmer than membrane suits, but as with any compromise, they are not perfect in every aspect.

Seals: Neoprene, Latex, or Silicone

Neck and wrist seals are crucial for keeping water out.

- Neoprene seals are durable but may stretch over time.\

- Latex and silicone seals are more flexible and easier to replace.

During training, you learn how to manage and maintain them.

How to Choose the Right Suit?

Your choice depends on:

- Water temperature\

- Dive duration\

- Conditions (currents, ice, etc.)\

- Travel needs

If possible, try different models before buying. Comfort is very important.

Dry Suit Diving Training

Unlike wetsuit diving, dry suit diving requires additional training.

You can take courses like PADI Dry Suit Diver or SDI Dry Suit Diver. In my case, I completed the SDI course through another diving association.

With a wetsuit, you just adjust your weights and go diving. With a dry suit, you must learn new skills.

What Do You Learn?

Air inside the dry suit compresses and expands with depth, just like in your BCD or lungs. You must learn to control it.

Main skills include:

- Managing air in both the dry suit and BCD\

- Preventing suit squeeze during descent\

- Proper body position for releasing air during ascent\

- What to do if you turn upside down and air moves into your legs

It sounds complicated, but with practice it becomes natural.

Personal Experience

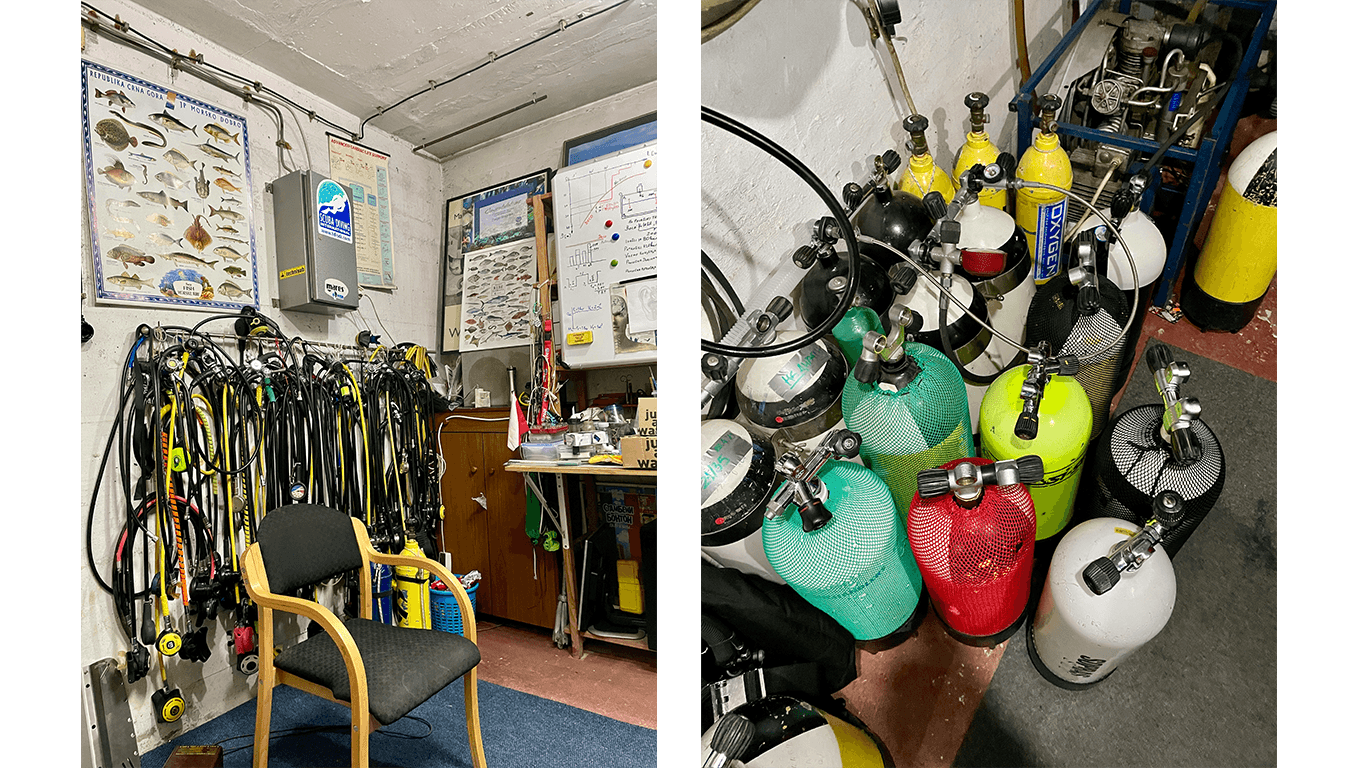

Belgrade has only a few dive centers. I contacted three, and only one replied - luckily, that was enough.

We met at their dive base, located in a basement but very professional and atmospheric. We discussed my experience, equipment, and training plan. We even had some rakija before scheduling theory and pool sessions.

Theory was presented in lectures. I also reviewed PADI materials I had access to from my Divemaster certification.

Pool training was interesting - we practiced in a public pool while kids were learning to swim nearby. Diving in a dry suit felt easier than expected, but very different.

I used a rental membrane suit - Ursuit Softdura. It had a front zipper, thigh pockets, and built-in boots.

It also had a P-valve - a special valve for... physiological needs during long dives. I didn't test it 😅

During the first session, I noticed water leaking through a wrist seal. For open water, gloves with ring systems were planned, but I asked for one more session to be safe.

Finally, we scheduled a dive at Ada Lake.

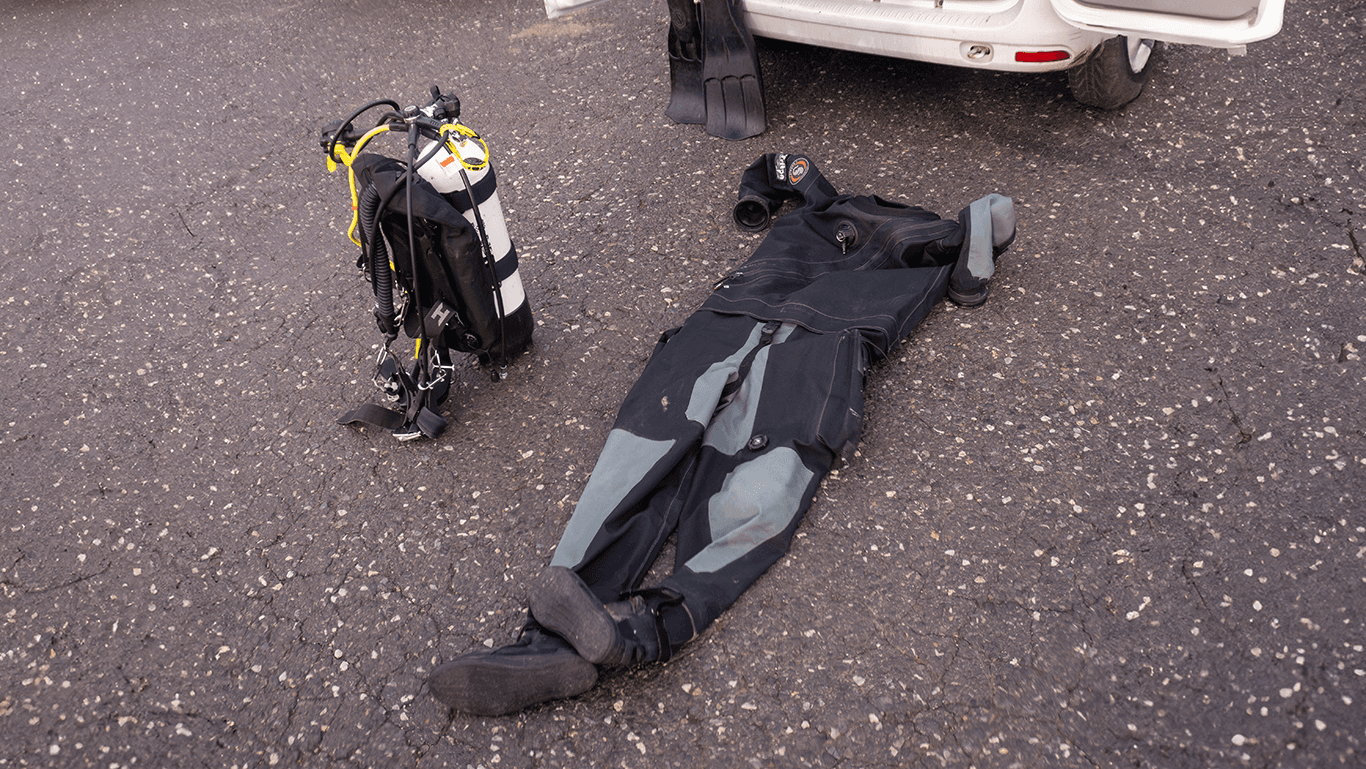

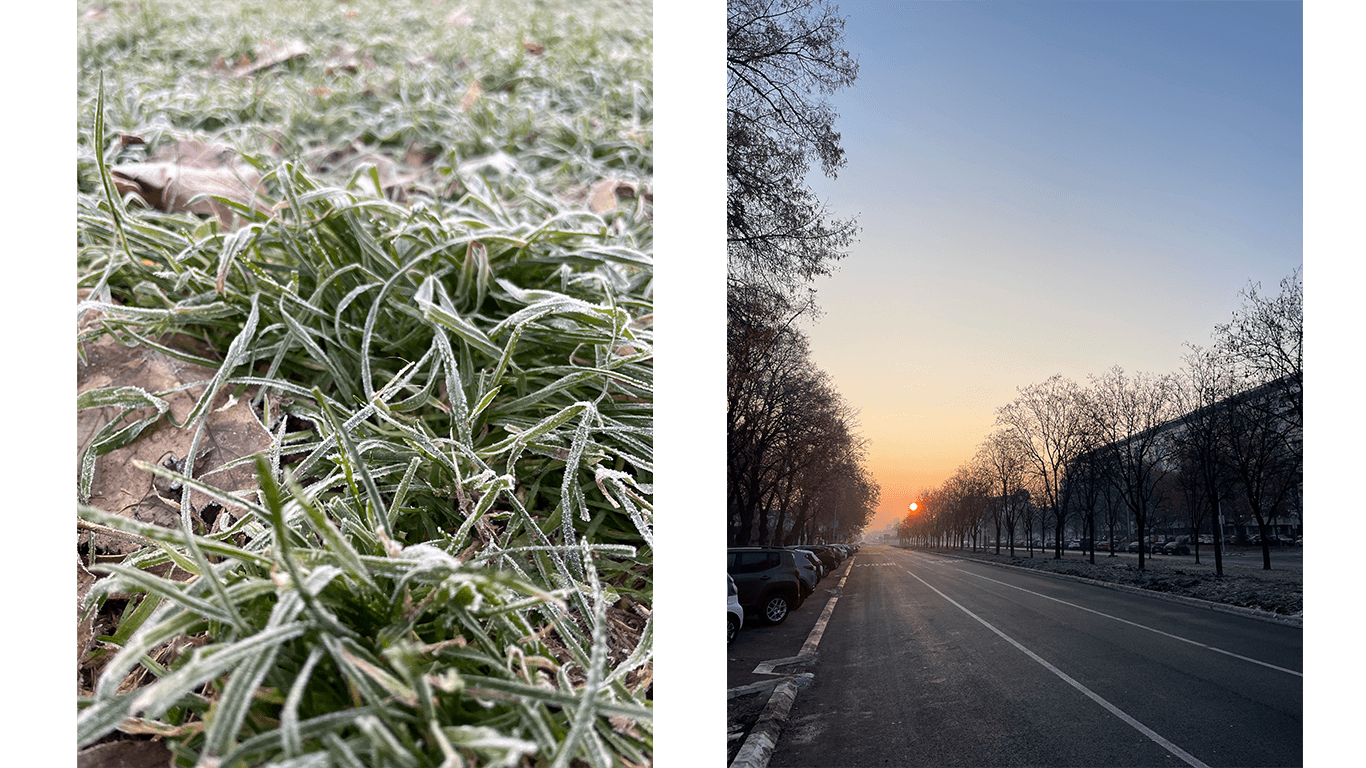

Last Sunday of 2024. +2°C outside. Frost on the grass. We gear up in a quiet park near the lake. Surreal moment.

My buddy entered first and showed floating ice. I laughed nervously and followed.

The water was freezing - but I stayed warm inside the suit.

Underwater life was minimal. A few crayfish, some plants, light rays through cold water. But the goal was simple: understand what winter diving feels like.

Conclusion

Dry suit diving is a completely different experience.

At first, everything feels unusual. But once you understand buoyancy control, it becomes enjoyable.

Yes, there are extra courses, higher costs, and more maintenance. But after my first cold-water dive, I realized it was worth it.

Now I know that limits in diving are not about weather - they are about equipment and skills.

Maybe one day I'll move into technical diving. Who knows? 😉