Deep Diving

What is deep diving?

Introduction

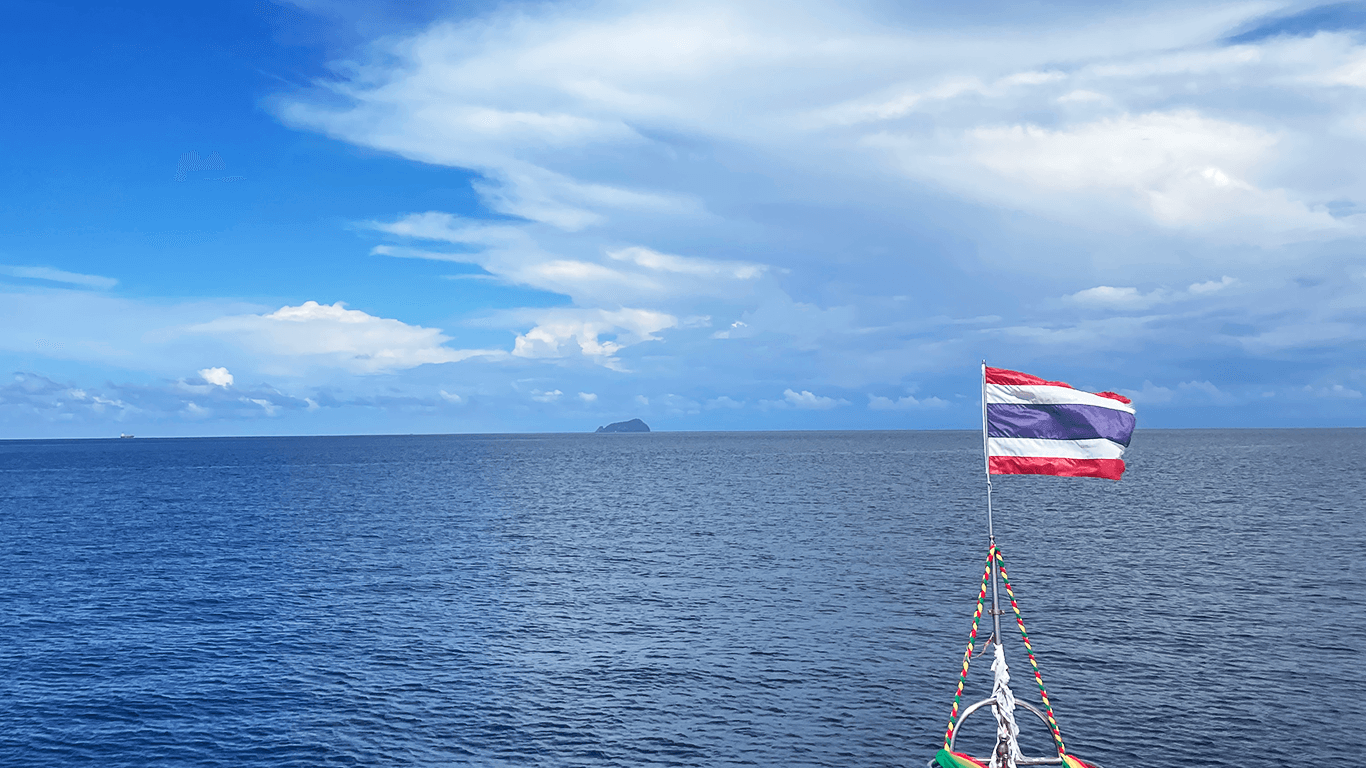

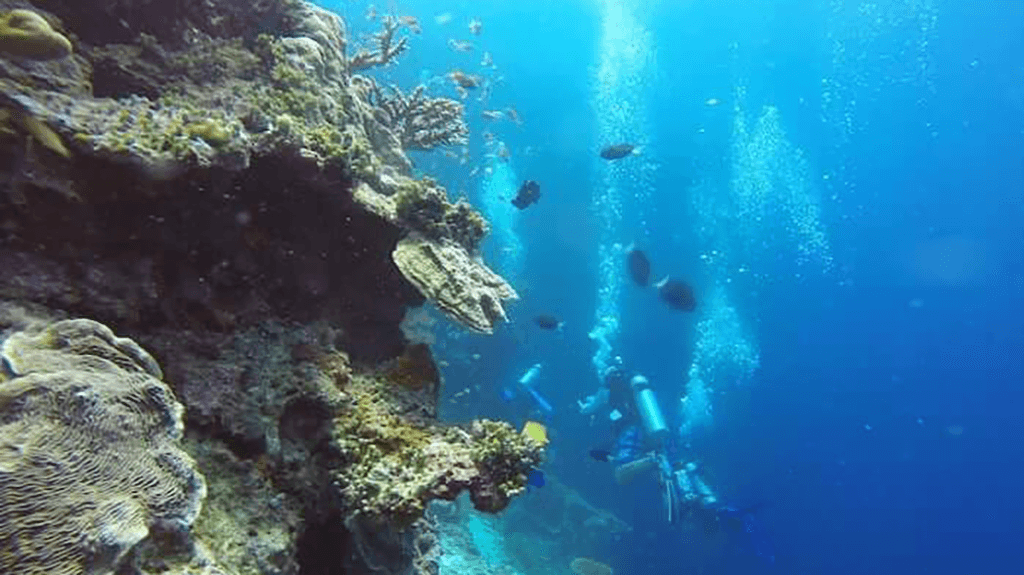

Why dive deep at all? You can enjoy beautiful corals and colorful fish already at 5 meters.

Deep diving is a way to achieve specific goals. Divers go deeper to see, do, or experience something that is not available at shallow depths.

It is also a chance to explore new locations. The Deep Diver certification gives access to new dive sites and different underwater activities.

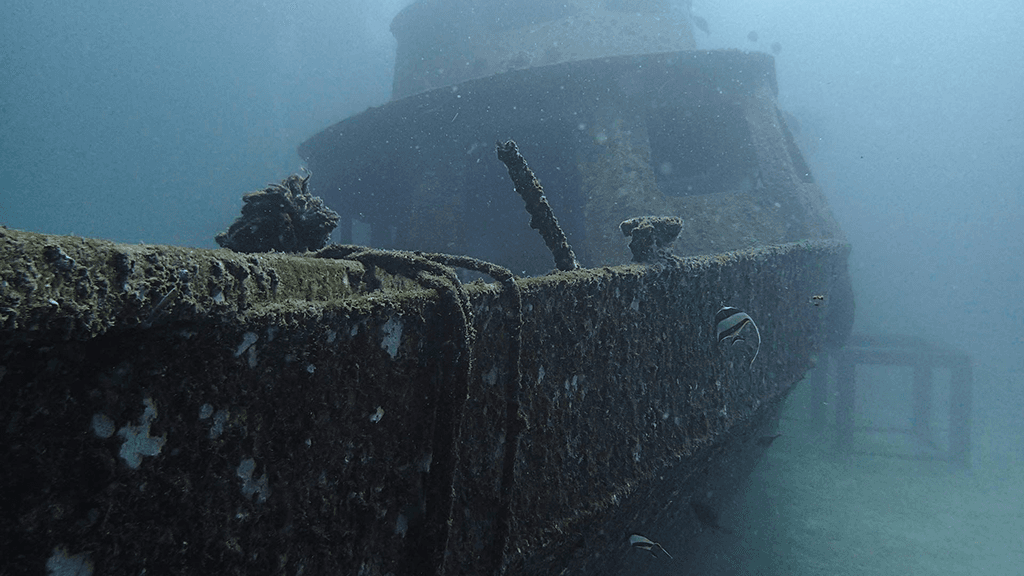

Large, well-preserved wrecks are often located at greater depths. Exploring them requires deep dives.

The deep-water environment also allows you to meet marine life adapted to darker and deeper conditions - species that rarely appear in shallow water.

Many drift dives take place in ocean currents that are weaker or absent in shallow areas. That is why drift dives often include deeper exploration along walls or reefs.

This course is an exciting and important step that opens the world of deep diving. It teaches key skills for safe and confident diving at depth.

In this article, I will explain what deep diving is about.

What Is a Deep Dive?

In recreational diving, a deep dive is considered any dive deeper than 18 meters and up to 40 meters.

Although the maximum depth in the PADI Deep Diver course is 40 meters, in practice 30 meters is often considered the optimal depth for most deep dives. There are several important reasons:

-

Below 30 meters, bottom time becomes very limited, even when using a dive computer and enriched air, in order to stay within no-decompression limits.

-

Deeper than 30 meters, the risk of decompression sickness (DCS) increases because you are closer to no-decompression limits.

-

At around 30 meters, some divers may start feeling mild nitrogen narcosis. It usually does not strongly affect most divers at that depth, but it is better to avoid the risk when possible.

-

The deeper you go, the darker it becomes. In temperate waters, light decreases significantly around 30 meters. Marine life also becomes less diverse, and it is harder to see details. In some freshwater lakes, light barely reaches even 30 meters.

Goals of Deep Diving

When planning a deep dive, it is important to have a clear and specific goal.

A proper goal could be: - Exploring a specific part of a wreck\

- Observing or photographing a particular marine creature\

- Exploring an underwater tunnel\

- Performing training exercises

Deep dives are not done to chase adrenaline or break depth records. Diving to greater depths must always be planned and justified.

Experience should be gained gradually, following safety rules, completing proper training, and using the right equipment.

Trying to set personal records without training and experience can lead to serious consequences. In diving, safety always comes first.

Safety in Deep Diving

The Deep Diver certification gives you responsibility for determining your personal depth limits. Five factors must be considered:

Environment

What is the visibility? Water temperature? Is there current? Are you diving at altitude? All these factors affect your maximum depth decision.

Your Training and Condition

How many dives have you done in similar conditions? Do you have experience at the planned depth? How do you feel today? Any medical issues?

These questions are important before every dive, especially deep dives.

Previous Dives

Have you already dived today? Does your dive computer allow another dive to this depth within no-decompression limits?

Medical Support

How far is the nearest medical facility? Where is the nearest recompression chamber? Emergencies are not planned, but we must be prepared.

Your Buddy

What is your buddy's experience level? How does your buddy feel today? Diving is teamwork. Always consider both yourself and your partner.

Deep Diving Techniques

Like any specialized activity, deep diving has its own techniques.

Buddy Contact

Losing your buddy is a serious mistake.

At shallow depths, you can ascend, meet at the surface, and continue. In deep diving, limited air and bottom time make this difficult. Ascending usually means ending the dive.

At depth, you depend on your buddy's equipment and support. Staying close is not just important - it is critical.

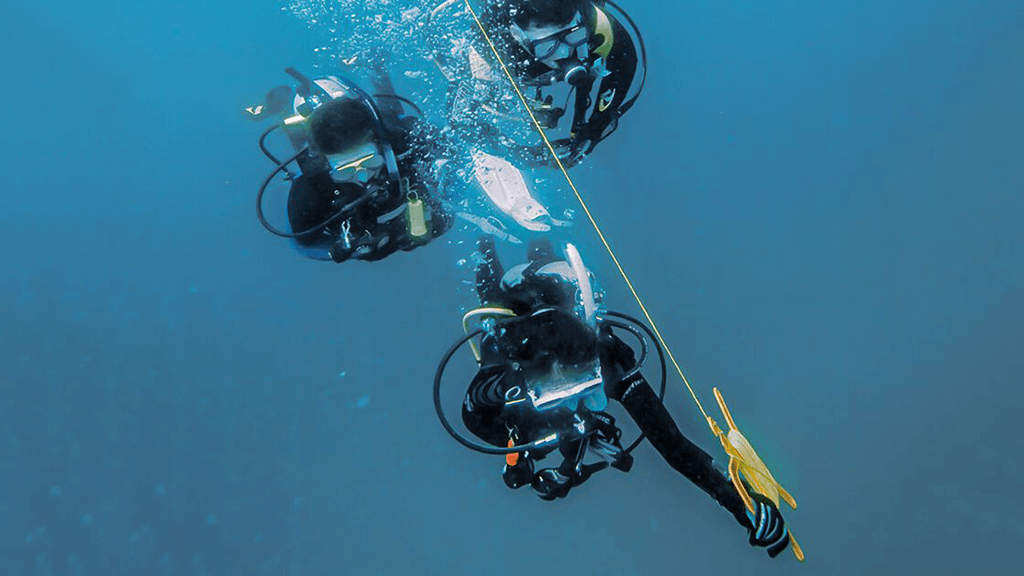

During descent and ascent, try to stay face-to-face at the same level. Stay closer than you would on a shallow dive.

Neutral Buoyancy at Depth

Your buoyancy changes during descent at any depth. However, at greater depths, buoyancy changes per meter become less noticeable because gas density changes more slowly.

I explained this in more detail in my article Atmospheric Pressure in Diving.

Descending Head-Up Position

Descending vertically with your head up and fins down helps prevent dizziness and disorientation. It also makes equalization easier.

Controlled Descent and Ascent

Avoid rapid descents and ascents.

Fast descent may cause ear, sinus, mask, or dry suit squeeze if you cannot equalize quickly.

Fast ascent can cause you to skip the safety stop and increase the risk of DCS or lung overexpansion injuries.

Ascent Rate

Always follow a safe ascent rate. Do not exceed 18 meters per minute, or go slower if your dive computer recommends.

When ascending, look up and stay aware of your surroundings.

Breathing Technique

Breathe slowly and deeply. This is important for all diving, but especially at depth.

At 30 meters, air consumption is much higher than at 10 meters because air is denser. It may feel like your air is running out quickly.

Check your pressure gauge regularly to avoid running low on air.

Nitrogen Elimination

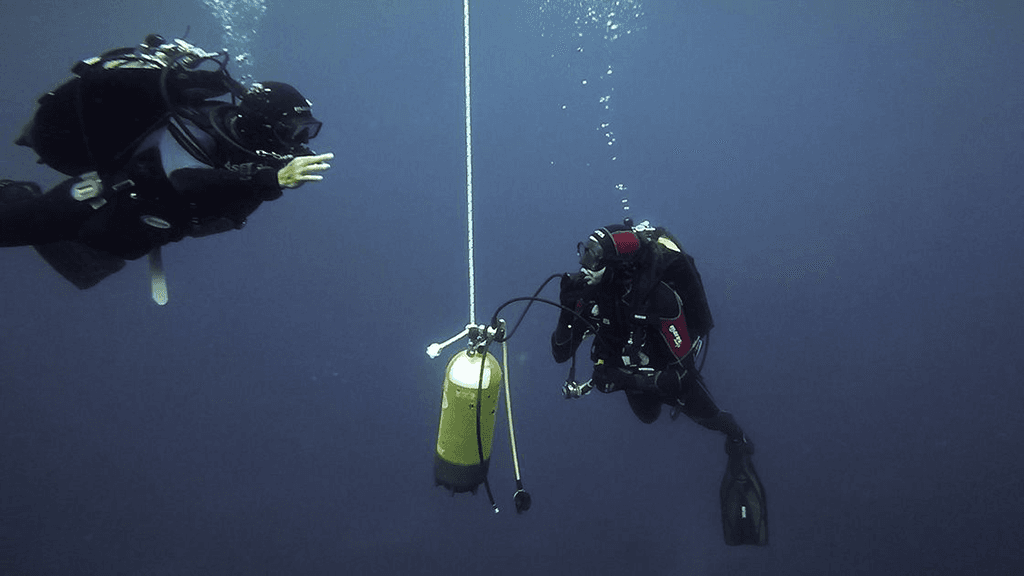

After every dive, make a safety stop. It reduces the risk of DCS by allowing excess nitrogen to leave the body.

A 3-minute stop at 5 meters significantly reduces bubble formation --- even more effectively than simply slowing your ascent.

Types of Deep Dives

Two common types require special attention:

- Drift dives (with current)\

- Wall dives

Deep Drift Diving

Drift dives can be physically easier because you move with the current. However, they require good coordination.

Important recommendations:

-

Use a dive boat: It is safer and easier to manage deep drift dives from a boat.

-

Synchronized start: Enter, descend, and ascend together with your buddy.

-

Choose descent method carefully: Some entries are done with inflated BCD, others with air released for immediate descent. The whole group should use the same method.

-

Use a surface marker buoy (SMB): It marks your position and can help during ascent. Keep equipment streamlined to avoid entanglement.

-

Monitor air and no-decompression time carefully: Maintain larger air reserves, especially because safety stops are required.

Deep Wall Diving

Wall dives can be breathtaking, especially in clear water. Follow three main rules:

-

Control depth: It is easy to lose depth awareness in clear water.

-

Stay near the wall: It helps orientation, but keep enough distance to avoid damaging marine life.

-

Use the wall as a reference during ascent: It can help you perform a safety stop at 5 meters without a descent line.

Nitrogen Narcosis

At around 30 meters, some divers may experience mild nitrogen narcosis.

Narcosis happens when breathing air under increased pressure. Nitrogen affects the nervous system.

Symptoms vary between individuals and even between dives.

Narcosis itself is not dangerous. The danger is how it may affect behavior and decision-making.

Symptoms (what you feel):

- Slow thinking\

- Poor concentration\

- False sense of safety\

- Short-term memory issues\

- Euphoria\

- Drowsiness\

- Anxiety

Signs (what you observe in others):

- Unsafe behavior\

- Slow reactions\

- Ignoring safety procedures\

- Confusion

Structure of the "Deep Diver" Course

The course includes at least four deep dives in open water.

Students perform practical exercises and complete theoretical training.

Some dives may be credited if you already completed certain programs like Advanced Open Water.

Conclusion

The Deep Diver course is an exciting step for those who want to explore deeper parts of the ocean.

It builds knowledge and skills for safe and confident diving at depth. Deep diving is a challenge, but with proper training, experience, and respect for safety, it becomes a rewarding adventure.

The ocean always demands respect. Keep learning, gain experience gradually, and explore deeper with confidence and responsibility.