Atmospheric Pressure in Diving

What happens to the body when we go underwater?

Home/Blog/Atmospheric Pressure in Diving

When a person goes underwater, they usually feel excitement, maybe a little fear, joy, and curiosity. But in this article I want to talk about something more important — what you must understand to make your dive safe and comfortable.

Atmospheric Pressure

All of us are constantly under pressure. Right now, the air around you is pressing on your body. At sea level, air pressure is almost constant and is equal to 1 atmosphere or 1 bar (Technically there is a small difference between a bar and an atmosphere, but it is so small that divers treat them as the same).

So, 1 bar is the pressure created by the whole column of air above us.

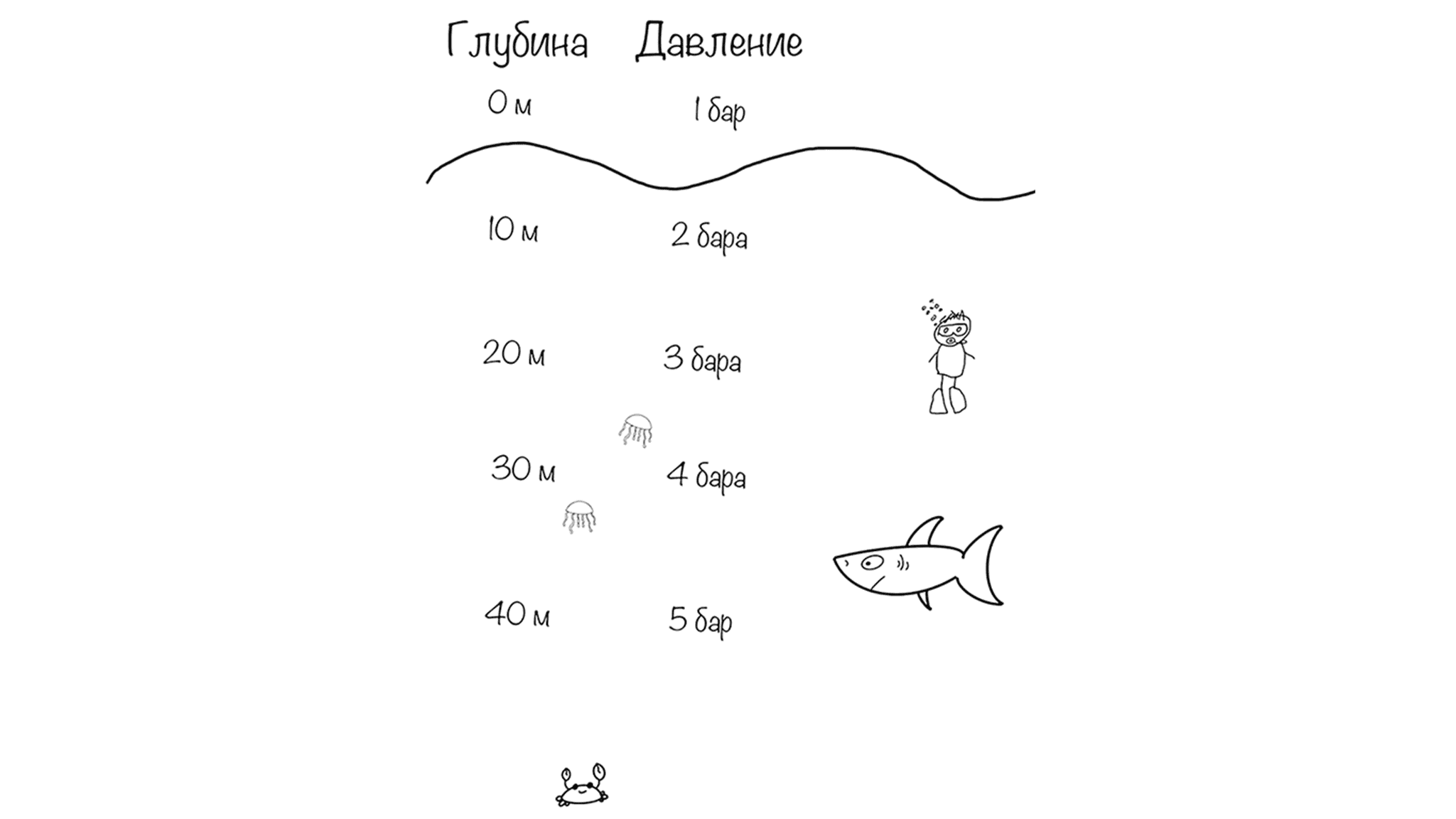

Underwater, a diver experiences even more pressure. Your BCD may feel tighter, your mask may fog, and the absolute pressure increases because water also has weight. The weight of the water adds to atmospheric pressure.

Water is much denser and heavier than air. A 10-meter column of salt water creates the same pressure as the entire atmosphere above us.

This means:

- At 10 meters — pressure is 2 atmospheres

- At 20 meters — 3 atmospheres

- At 30 meters — 4 atmospheres

- At 40 meters — and so on

Pressure increases by 1 atmosphere every 10 meters during descent. It decreases by 1 atmosphere every 10 meters during ascent.

Fresh water is slightly lighter than salt water, so you need about 10.3 meters of fresh water to increase pressure by 1 atmosphere. The difference is small, but it’s good to know.

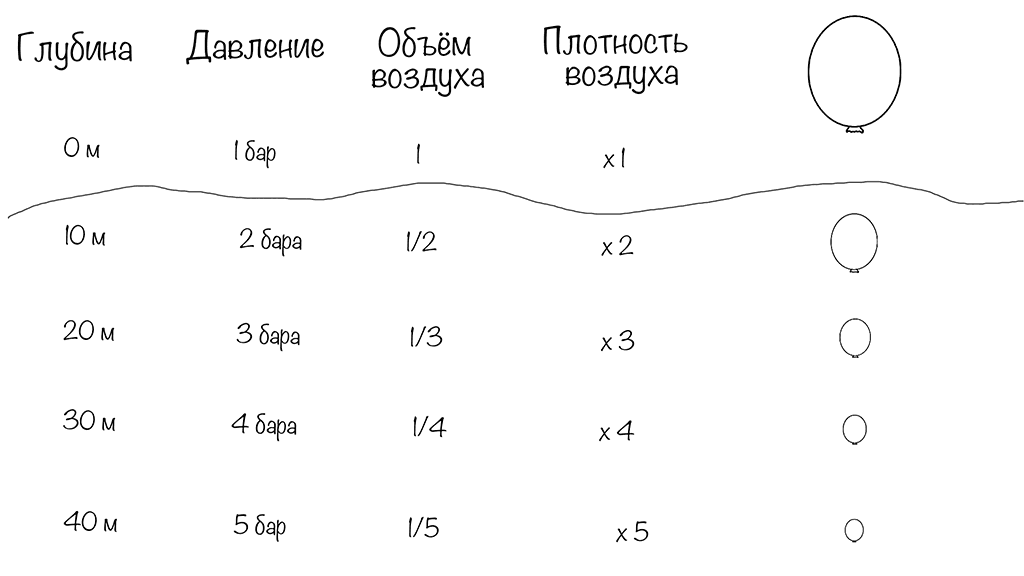

Relationship Between Pressure, Volume, and Air Density

Water almost does not compress. Its volume and density do not change much under pressure. Since the human body mostly consists of water, pressure does not affect most of our body directly.

But air is different. When pressure increases, gas volume decreases. Gas density increases because the same number of molecules now occupy a smaller space.

This affects:

- Ears

- Sinuses

- Lungs

- Mask

- Dry suit

- Buoyancy control

- Air consumption

Let’s look at a simple example.

Imagine a balloon that contains 3 liters of air at the surface.

- At 10 meters (2 atmospheres), its volume becomes 1.5 liters.

- At 20 meters (3 atmospheres), it becomes 1 liter.

- At 30 meters, even smaller.

Every 10 meters, the volume changes according to pressure.

Now imagine the opposite situation.

If you inflate a balloon halfway (1.5 liters) at 30 meters, where pressure is 4 atmospheres, and then ascend:

- At 10 meters, the balloon will already be fully inflated.

- If you continue to ascend, the expanding air will make the balloon burst.

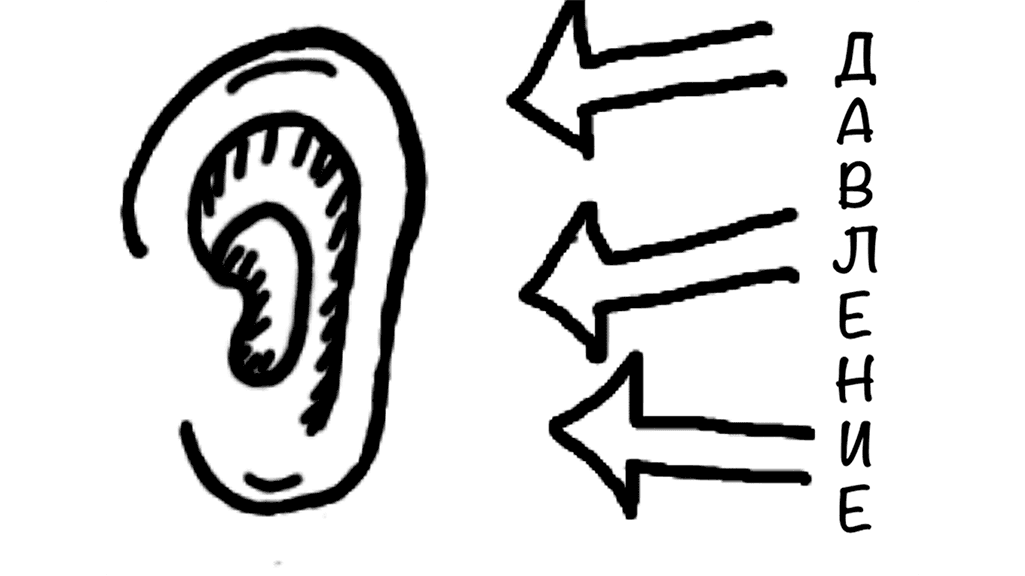

Reaction of Air Spaces in the Body

Most of the human body consists of water, but we have air spaces inside and around us:

- Ears

- Sinuses

- Lungs

- Mask

- Dry suit

A pressure imbalance happens when the pressure outside an air space is higher than inside it. When air volume decreases, water pushes harder on the surrounding tissues. This causes discomfort.

If you do not equalize, you will feel squeezing. Discomfort in diving is never good. If ignored, it can lead to injury.

The solution is simple: add air to these spaces during descent. This balances internal and external pressure.

Let’s start with the ears.

Anyone who has flown on an airplane knows the feeling of blocked ears during takeoff or landing. This also happens because of pressure changes.

To equalize:

- Pinch your nose

- Gently blow

This moves air into the middle ear and balances the pressure.

There are other methods, like moving your jaw or swallowing. But gently blowing into your nose is the most common and effective way.

It is very important to equalize during descent to prevent barotrauma. At the same time, do it carefully. Too much force can also cause injury.

Remember:

💡 Equalize early and often during descent

Do not wait until you feel pain. If you equalize every meter (or even more often), you will not feel discomfort.

What About the Mask?

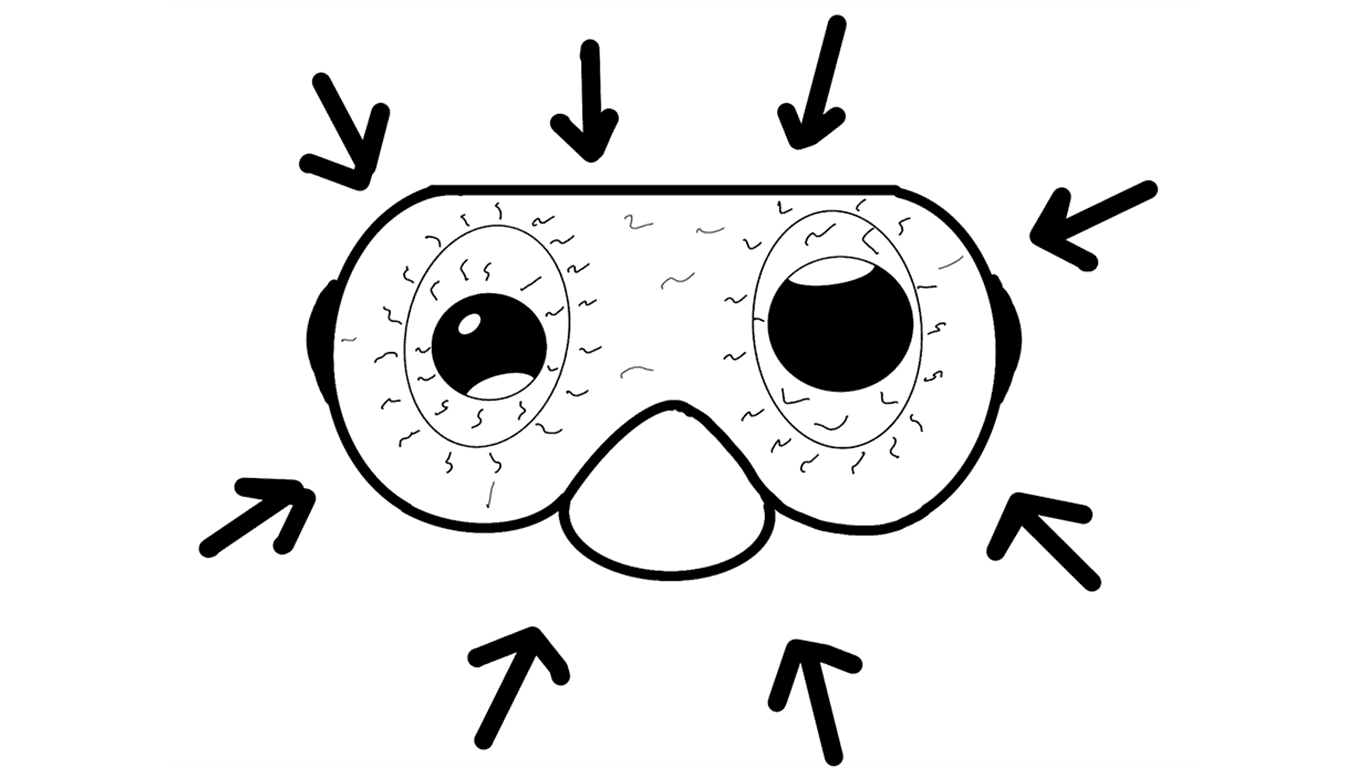

Air inside the mask also compresses during descent. If you do not add air, the mask can squeeze your face. Small blood vessels may break, causing red eyes or bruising around them. It looks unpleasant but usually heals without serious problems.

To avoid this, simply exhale a little air into your mask through your nose while descending. Then you can safely take selfies after the dive 🙂

And the Lungs?

Lungs react to both increasing and decreasing pressure.

During descent, higher pressure does not directly harm your lungs because you breathe air supplied at the same surrounding pressure.

But during ascent, expanding air can be dangerous.

Remember the balloon example. If you ascend while holding your breath, the expanding air in your lungs can cause serious injury.

That’s why there is one very important rule in diving:

💡 We never hold our breath

As you can see, even though we constantly experience pressure changes underwater, they do not cause serious problems if we understand how it works and follow basic diving rules.